Show, Don’t Tell

Everyone craves good stories. We want to listen to good stories. We want to be captivated as the story unfolds. We also want to tell our own stories in a way that intrigues, compels, and conveys our ideas clearly and powerfully. Writing a good story is much more than just recording our thoughts. A good story, one worth telling and listening to, must be crafted in such a way as to create a vivid picture in the reader’s mind. We call this “showing”.

Showing involves describing characters, objects, and settings vividly. But showing is more than just description. Showing allows a living, breathing character to move, react, and interact with realistic objects within a setting so believable the reader becomes immersed in the tale. Showing makes a story come alive in the reader’s imagination. Conversely, telling states facts.

Every writer, no matter their age or level of experience, needs to be reminded often: Show! Don’t tell! Lots of telling and a little showing is age-appropriate for the young writer. However, the default for maturing writers should be to show more than tell whenever possible. And it is always possible!

Showing is a vital writing skill. Showing hooks readers and keeps them hooked until the end of the story.

What does it look like to show versus tell?

Telling gives information.

Showing creates an image.

Telling is direct. It robs the reader of the joy of drawing conclusions.

Showing helps readers make connections, supplying clues they can piece together to uncover truths about a character, setting, object, or story plot.

Telling states the facts as the author knows them.

Showing makes a character, setting, or object come alive to the reader, allowing them to visualize a scene through the complex filter of their own understanding and experiences.

Telling delivers a lecture and can leave a reader feeling belittled.

Showing allows readers to experience the joy of thinking, visualizing, and discovering meaning beyond the words on the page, leaving them feeling trusted and intelligent.

Telling reports.

Showing reveals.

Every sentence in a story has two purposes:

Move the story action forward

Create a visual image for the reader

If a writer successfully crafts a sentence that does both, it will inevitably show far more than it tells. Even younger writers can be taught how to do this through modelling and practice.

In my third-grade classroom, we practice showing versus telling often. At least three times a week, I provide a sentence prompt. The sentence tells some piece of information. Students are asked to show the same information. After they share their new version, we discuss what they did to craft visually vivid sentences. Each time we attempt to show, not tell, we discover new techniques to help us create a visual image for our readers. Here are a few strategies my third graders have used successfully. Several of my students are second-language English learners. I doubt you will be able to differentiate their writing from that of their first-language English peers.

Strategy 1:

Put yourself or your main character into the description, interacting with the object, character, or setting. What did the character hear, see, smell, taste, or touch? Use specific sensory words to make the reader feel like they are part of the story.

Telling: It was a stormy day.

Showing: The lightning roared down from the clouds. The rain poured down onto the streets. I hurried up and opened the umbrella and put it over my head.

(Aiden, age 9)

Strategy 2:

Use onomatopoeia (sound effect words). The sense of hearing is an important and sometimes overlooked part of any scene in a story.

Telling: My legs ached from running so hard.

Showing: Thump! My legs crashed as the black-coated man advanced. I stood and ran even though my legs felt like fire. (Harper, age 9)

Strategy 3:

Include dialogue or a thought. Have your character say (or think) something that shows how they feel about the character, object, or setting described.

Telling: The creature was ugly.

Showing: The creature scratched me with (his) broken claw. He spat goo from his mouth on me. Eww! I better take a shower! (Ava, age 8)

Strategy 4:

Use specific, descriptive words to show something important about the character, setting, or object.

Telling: The rainbow was beautiful.

Showing: The rainbow beamed red, orange, yellow, green, blue, and purple. I danced under it. The sun beamed on the rainbow, causing more light. (Claire, age 9)

Strategy 5:

Use strong verbs that show clear, specific actions. Avoid words like go, went, do, did, was, were.

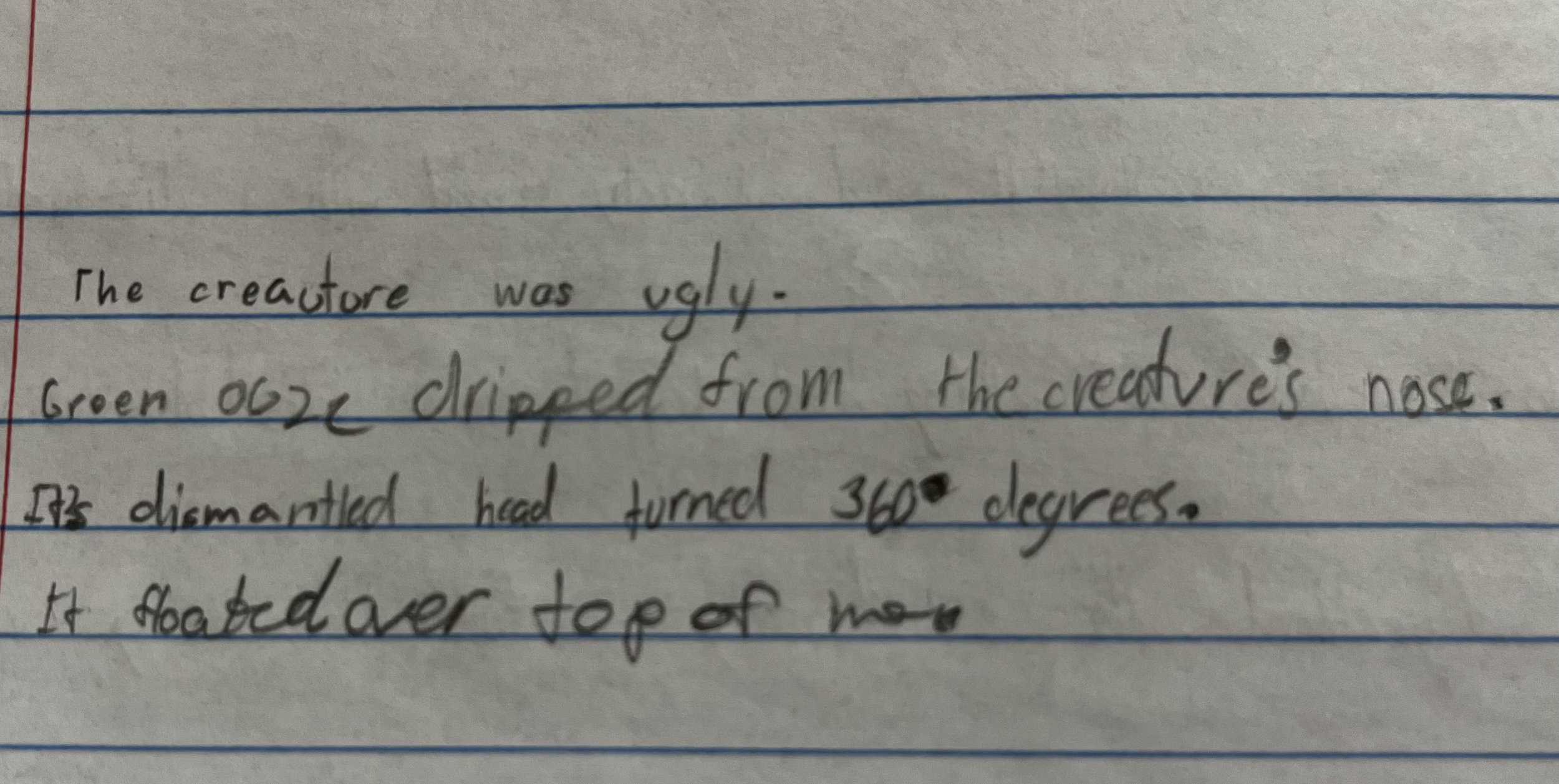

Telling: The creature was ugly.

Showing: Green ooze dripped from the creature’s nose. Its dismantled head turned 360 degrees. It floated over top of me. (Omar, age 8)

Telling: The boy fell down.

Showing: The boy tumbled down the stairs, slid on the wood, and hit his head on the wall. (Caden, age 8)

Strategy 6:

Avoid sentences that begin with “There/it was/is”. Instead, put the subject at the beginning of the sentence and use vivid verbs and specific adjectives to describe the subject.

Telling: It was a sunny day.

Showing: The birds were chirping. The sun was shining. Laughter filled the air. (Synthia, age 8)

Young writers intuitively understand that showing is a key element of any good story. They know this because human beings are wired to appreciate effective storytelling. When you read mentor texts with young writers, ask: “What did the author do to reveal rather than report?” Children who are taught to appreciate well-written literature and can pinpoint the strategies authors use to craft effective sentences transition to writing their own “show, don’t tell” sentences more confidently.

Ultimately, young writers will begin to use the skill of showing in longer writing pieces. Harper created the following description to show her favourite season.

Fall is the best season, clearly. Crunch! The leaves snap underfoot as I take a walk outside. The cold wind flows through my hair. In later fall, close to winter, I like to jump and lay in the small clumps of snow. The fall weather is chilly but not too cold. I love the display of crimson, lemon, and mandarin colours. I love all the colours of fall. I also like the scent of fresh crisp air. Fall is clearly the best.

Harper (age 9)

Harper crafted this paragraph after we had read Melissa Sweet’s book, “A Little More Carmine”. You can see she put herself into the scene, moving and interacting with the fall leaves, revealing something about both the scene and her personality. In addition, she used vivid colour words to describe the leaves, strong verbs to convey action, and a sound effect word to make her description come to life.

*For other mentor text suggestions, click here.

“Show, don’t tell” is good advice for any writer, young or old. Don’t wait until your young writers have written hundreds of ineffective sentences before you teach them this skill.

Start early.

Start today.