Showing - Words Matter

“There is something delicious about writing the first words of a story. You never quite know where they’ll take you. ”

You’re reading. Your mind is immersed in another place and time. You see, hear, taste, smell, and touch what the character sees, hears, tastes, smells, and touches. Your heart aches with each failure. It leaps with each victory. But then the inevitable happens. You have to stop reading, perhaps for some inconsequential task such as making dinner, driving to work, or getting the kids ready for soccer practice. As you tear your eyes away and watch your hands close the cover, you feel yourself being clawed back to a smaller, duller reality.

When a writer can create a world in words so vivid that reality pales in comparison, you know you are reading the work of someone who has mastered the craft of showing versus telling.

Showing is the most essential of all creative writing skills.

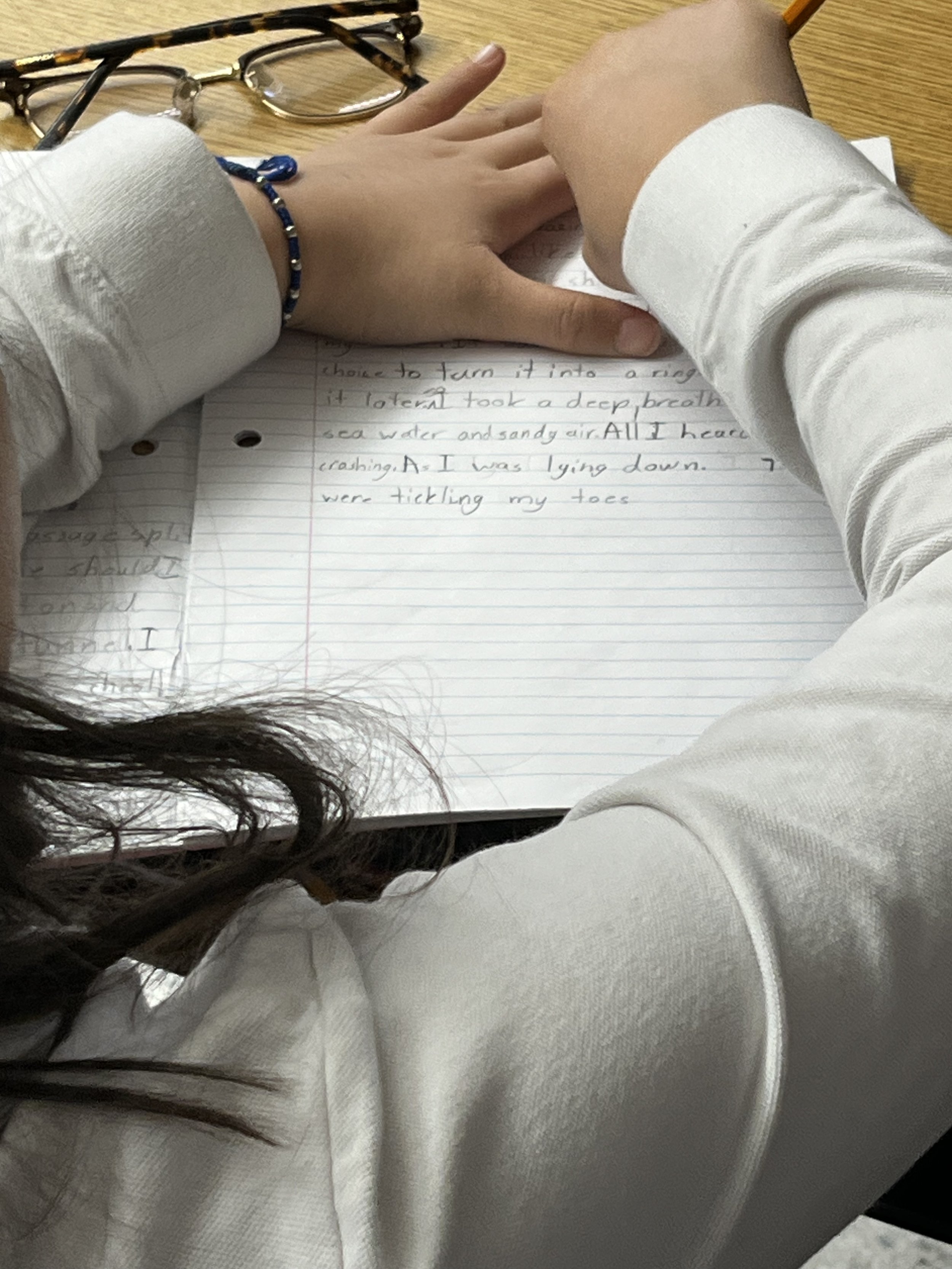

Showing is descriptive writing that hooks readers and keeps them hooked.

The average age of debut novelists is 36. However, many authors were first published much later than that. Frank McCourt, author of Angela’s Ashes, was 60. Laura Ingalls Wilder, who wrote the Little House on the Prairie series, was 65. The oldest novelist on record is Lorna Page, whose thriller, A Dangerous Weakness, was published when she was 93. The book was only published because Lorna’s daughter-in-law found the manuscript and couldn’t put it down. Lorna was a word world builder who knew how to show, not tell.

What separates good writers from great writers? A great writer crafts new yet fully believable worlds out of ordinary words.

If we can teach our youngest writers this essential skill when they first learn to create sentences, imagine the calibre of stories they’ll produce long before their mid-thirties and throughout their lifetimes.

In a previous post, I suggested that every sentence in a story has two purposes:

Move the story action forward.

Create a visual image for the reader.

In other words, every sentence carries weight and importance. The words we use to create sentences must be selected carefully so that each sentence becomes part of the larger word world we build for readers to visualize.

There is no reason to wait until a child is “old enough” to teach them how to show versus tell. You can start by reading well-crafted children’s literature aloud, even before they can read independently. You can encourage them to “show” by describing essential details when they speak. You can model the art of elaborative description through conversation as you share ideas and questions, demonstrating how to draw out details and describe them well. Developing writing creativity starts much earlier than the physical act of writing itself. Creativity begins with learning to think like a writer and then steadily building the capacity to do the hard work of fleshing out the details.

Children who are encouraged to read good literature and taught how to engage in meaningful conversations from a young age quickly understand how crucial description is to good storytelling. Once they can write simple sentences, you can deliberately model how to craft sentences that show more than tell.

Sentences that show are:

Specific

Concrete

Paint a picture in words for the reader

Throughout the next several blog posts, I will outline various techniques you can model to help your young writer craft descriptions that show. The skill of showing is not simple. It is complex. Every serious writer constantly works to improve in this area; many writers never feel they have mastered it. This does not mean it is an unattainable goal. It means we must start teaching this skill to our young writers as early as possible.

Showing is important in every stage of the writing process. Many details must be elaborated upon, from brainstorming and planning to writing the first draft, revising, and creating the final draft. Showing brings clarity, directs word choice, affects author's voice, and determines the figurative language we use. How we show what we mean plays a role in every decision we make as writers.

Some of the techniques I will discuss in future posts include:

Word choice - choosing powerful verbs paired with specific nouns

Sensory imagery - the importance of writing to show the five senses

Subject sentence starters - the “magic” way to break the habit of starting a sentence with “there was/is”

Elaborative detail - adding descriptive information to bring characters or settings to life

Figurative language - similes, metaphors, hyperbole, and personification

Dialogue - using dialogue to build characters and describe settings

Does every sentence in a story need to show? No. However, a great writer learns early that sentences must show more often than they tell. The earlier we model this for young writers, the sooner they will become great writers.